CANADA HISTORY - DOCUMENTS COLONIAL

1838 Elizabeth Lount Open Letter to John Beverley Robinson, Chief Justice of Upper Canada

Analysis of the Document - (The Document follows below the Analysis)

The Open Letter written by Elizabeth Lount in 1838 to John Beverley Robinson, the Chief Justice of Upper Canada, stands as one of the most poignant and powerful documents of its time. A letter penned by a grieving widow, it was both a personal appeal and a public condemnation of the colonial justice system that had sentenced her husband, Samuel Lount, to death. Samuel Lount had been a leading figure in the Upper Canada Rebellion of 1837, a movement led by William Lyon Mackenzie that sought to challenge the political oligarchy of Upper Canada and demand responsible government. The rebellion, although short-lived and ultimately unsuccessful, sparked a harsh crackdown by the colonial authorities, leading to the execution of several key figures, including Samuel Lount and Peter Matthews. Elizabeth Lount’s letter, written in the aftermath of her husband's execution, was a powerful critique of the colonial establishment, particularly its judicial system, and remains a critical document in understanding the human cost of the rebellions and the broader political struggle for reform in Upper Canada.

Elizabeth Lount’s Open Letter is deeply personal but also profoundly political. In her letter to Chief Justice Robinson, she pleads for justice and humanity, challenging the morality of a legal system that would sentence a man to death for participating in what she believed was a just cause. She framed Samuel Lount not as a traitor, but as a man who had stood up for the rights of the people, seeking to address the injustices perpetuated by an entrenched political elite. Her words were filled with sorrow, anger, and a sense of betrayal, directed not only at the individual who had condemned her husband but also at the broader colonial system that she believed had failed its citizens. Robinson, the Chief Justice and an ardent defender of the colonial status quo, represented everything that Lount and the other reformers had fought against—an unyielding oligarchy that governed Upper Canada without true representation of the people’s interests.

The Open Letter was significant for several reasons, both in its immediate impact and its long-term implications. It provided a rare, direct critique of the judicial and political authority in Upper Canada from the perspective of a woman, at a time when women’s voices were largely excluded from public political discourse. Elizabeth Lount’s decision to make her appeal public was in itself a powerful statement, reflecting both her personal desperation and her belief that the people of Upper Canada needed to understand the true nature of the colonial regime. She positioned herself as not only a grieving widow but as a representative of the suffering endured by many in the colony—those who felt oppressed by the unaccountable rule of the Family Compact, the small elite that controlled the political and economic life of Upper Canada.

The content of Elizabeth Lount’s letter also highlighted the human cost of political repression in the colony. The Upper Canada Rebellion had been a direct response to years of frustration among reformers who sought greater political representation, an end to the domination of the Family Compact, and more equitable governance. When the rebellion was crushed, the response from the colonial authorities was swift and severe. Leaders of the rebellion were executed, imprisoned, or forced into exile. Samuel Lount, who had played a significant role in organizing the rebellion, was captured and sentenced to death, despite numerous petitions for clemency. Elizabeth Lount’s letter is filled with raw emotion as she described the pain of watching her husband be condemned to death for what she saw as his righteous defense of liberty and justice. Her words underscored the human toll of political conflict, reminding her readers that behind every political movement and every rebellion, there are individual lives at stake—lives that can be destroyed by the whims of those in power.

The figure of John Beverley Robinson, to whom the letter was addressed, looms large in the history of Upper Canada. As Chief Justice, Robinson was not merely a judicial figure but a staunch defender of the conservative, colonial order. He was an influential member of the Family Compact, which had long governed Upper Canada in a way that marginalized reformers and silenced demands for greater democracy. For Robinson, the rebellion represented a threat not only to the established order but to the very stability of the colony. His role in sentencing Samuel Lount to death was consistent with his broader belief in the need to maintain order and suppress any challenge to British rule. Elizabeth Lount’s letter directly challenged Robinson’s role in this system, questioning not just the legal basis for her husband’s execution but also the moral and ethical responsibility of those in power. Her letter was, in essence, an indictment of the entire colonial justice system, which she believed had become an instrument of oppression rather than justice.

Beyond the immediate circumstances of the rebellion, Elizabeth Lount’s letter had broader implications for the political culture of Upper Canada and the future of reform in the colony. The public outcry over the executions of Lount and Matthews helped galvanize support for the reform movement, even in the aftermath of the failed rebellion. While the rebellion itself had been crushed, the harsh measures taken by the colonial authorities in its wake deepened the resentment many had toward the ruling elite. Elizabeth Lount’s appeal, coming from the heart of the conflict, played a role in shaping public opinion and keeping the cause of reform alive. In the years following the rebellion, demands for political change only grew stronger, culminating in the eventual granting of responsible government to Upper Canada in the 1840s. The letter thus stands as a reminder of the personal sacrifices made in the struggle for political reform and the ways in which these sacrifices contributed to the broader movement for democracy in Canada.

One of the most compelling aspects of the Open Letter is how it highlights the gendered dynamics of political and social struggle. In 1838, women were largely excluded from formal politics, yet Elizabeth Lount found a way to enter the public sphere through her personal tragedy. By framing her letter as both a personal appeal and a political statement, she was able to engage in a form of political activism that was otherwise denied to her as a woman. Her letter is one of the few surviving documents from the period that offers insight into the role of women in the political struggles of Upper Canada, showing how women, though often sidelined in historical accounts, played a vital role in shaping public discourse and advocating for justice.

In the long term, Elizabeth Lount’s Open Letter is significant for its contribution to the legacy of the Upper Canada Rebellion and the memory of those who fought for reform. Samuel Lount and Peter Matthews became martyrs for the cause of responsible government, and their executions are often seen as a turning point in the history of Canadian democracy. The rebellion, though a failure in its immediate goals, exposed the deep divisions within Upper Canadian society and the growing demand for political change. Elizabeth Lount’s letter captures the emotional and moral core of that conflict, reminding future generations of the human cost of the struggle for justice. It stands as a powerful document in Canadian history, not only as a testament to one woman’s grief but as a broader indictment of the colonial system and a call for a more just and equitable society.

In conclusion, the Open Letter of Elizabeth Lount to John Beverley Robinson in 1838 is a significant historical document that provides a deeply personal yet politically charged critique of the colonial justice system in Upper Canada. Written in the aftermath of the Upper Canada Rebellion, the letter offers a rare glimpse into the emotional toll of political repression and highlights the broader struggle for reform and justice in the colony. Elizabeth Lount’s letter is not only a memorial to her husband, Samuel Lount, but also a broader commentary on the political and judicial system that had condemned him. Her words resonate through history as a powerful reminder of the personal sacrifices made in the fight for responsible government and democracy in Canada. The letter, with its emotional appeal and its critique of the colonial order, continues to influence how Canadians remember the rebellion and the ongoing struggle for political reform in the country’s early history.

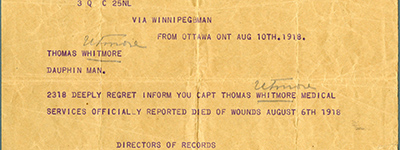

[published in the Pontiac, Michigan, Herald, June 12, 1838, two months after her husband Samuel was hanged for taking part in the Rebellion of 1897]

Pontiac, June 12, 1838

SIR: Woman cannot redress her wrongs. Her feeble arm is powerless; even were justice to be reached with certainty through fatigues in the tented field, and liberty be given to an oppressed, enslaved and insulted people, 'tis not woman who should lead the way. It belongs to the "lion heart and eagle eye" of your sex, sir, to lead in war, to maintain a people's rights, to do or die on redressing their wrongs, to save their country from oppression and slavery. But to you, sir, Canada can never look for assistance. It has been said by an eminent author that every man has his price, and however unjust the remark is with regard to others, I conceive it well applies to yourself.

In this letter, intended as a partial exposé of the sufferings of myself and family, and of the execution for treason of my beloved husband, Samuel Lount, M.P., I would remark that my husband was born in the state of Pennsylvania, in the year 1791, and emigrated to Canada when about 29 years of age. He had taken the oath of allegiance, and had become an adopted citizen of the Province. He was a reformer and a loyal subject. He had become familiar with the constitution and the laws of Great Britain, and where they were regarded and justly administered it always gave him pleasure. During his lifetime he had frequently been requested by his fellow citizens to become a candidate for a seat in the Provincial Parliament, but refused repeatedly. At length, however, he was taken up and elected. While in Parliament he became acquainted with the leading men of the country, and being a liberalist in his opinions, united his political fortunes with Doctor Rolph, Mr. Mackenzie, and other distinguished gentlemen, who beheld with regret the corruptions of the government. They saw a rich and fertile country, almost prostrate and ruined - a hopeful people possessed of the feelings and sympathies of men, trampled upon by the mercenary wretches, whose places in office gave them power. Year after year Canadian grievances became more alarming, until almost the entire population groaned for relief - groaned beneath the yoke of their bondage. This, sir, no one knows better than yourself. And while seated upon the judicial bench, enjoying one of the highest offices in Canada, you, together with others, conceived the noble thought of working a civil revolution in the Province, to give liberty to a people whose chains you have, since the outbreak of that war, most diligently labored to rivet yet closer upon them. He whom you have been instrumental in consigning to the grave, and whose spirit is pure as the angels in heaven, testifies to your guilt - a guilt despicable and most horrid - as friend, co-patriot, traitor and Judge! True it is that my dear husband, whom your laws have torn from me and from his helpless children, espoused sincerely the cause of reform. Had their plans succeeded, that reform would have been obtained - the Governor secured - and the Province freed without shedding of a drop of human blood. Had not the mistake been made for the rally, the arms of the Province would have been seized by the patriots, Toronto would have been taken by consent and Sir Francis held in their power to answer for his oppressions. Those with whom my husband acted were moved by the impulses of noble and generous sympathies. They panted not for offices, for those they enjoyed - they thirsted not for blood, for Canadians were their brothers - they were determined to drive a Nero from his throne, to rid Canada of a tyrant, and to effect a civil revolution that would give happiness and prosperity to the country. Had they been successful, Canadians to the latest posterity would have blest them. But, sir, all is not over yet. No government whose only acts are those of violence and cruelty, whose statute book is stained with the blood of innocent sufferers, and whose land is watered by the tears of widows and orphans, can long stand contiguous to a nation abounding in free institutions. 0 Canada, my own country, from which I am now exiled by a party whose mercy is worse than death - I love thee still. Destruction has overtaken thy brightest ornaments, and the indignant feelings of thy sons b their hearts, but they dare not give utterance to their thoughts. How many mothers have suffered, like m loss of a home and all that could make that home plea ant. This, however, could have been borne. They who love liberty, and prize their independence above all earthly things, regard not the loss of property. I do not write to excite your sympathy, for that I neither respect or covet. I write that Canada may know her children will not silently submit to the most egregious outrages upon private property, and even life itself. Sir, it beggars description, and is beyond my competency to relate my sufferings while a subject of Canada. For the generous acts of a brave and noble hearted man I have seen his son taken before his mother's eyes, tied like a galley slave and driven to prison as a felon - aye, more, I have seen the innocent youth covered with wounds received from a drunken and brutal soldiery whose election it was to do the work of the officials. I have seen my husband's house pillaged, and his parlor made a soldiers' camp, his property confiscated, and his heartbroken wife and six children cast upon the charity of the cold world. I have beheld the husband and father in prison, condemned to death without the least shadow of a crime against him. I ask in the name of my country, are acts like those to be tolerated by an English Government, or is there on this earth an Englishman who does not blush at the recital of such acts of cruelty?

Sir, the officers of the government of Canada, civil and military, are placed over the people without their consent. They form a combination too powerful for the prayers of an humble citizen to move. Be their acts however corrupt, the law is by themselves administered, and consequently they are beyond its reach; while if the private citizen offend he is neither safe in his property or person. If these things are so, I ask you, sir, how long will the people of Canada tamely submit? Will they not soon rise in their strength, as one man, and burst asunder the chains that bind them to the earth and revolutionize and disenthrall Canada from the grasp of tyrants?

Sir, savage nations respect my sex, and their female captives are treated with kindness. Your Governor and his Council, together with a majority of your party during the late difficulties neither respected private property nor harmless unoffending women. With him and his minions all were fit subjects upon whom to practise cruelty.

After my lamented husband had been convicted, I learned that Governor Arthur had visited the prison and it was hoped that mercy had called him thither. But there was no mercy in his obdurate heart - cruelty is the reigning demon of his passions. When Mr. Lount was arrested and carried bound to Toronto, I immediately repaired there, but was not allowed by the Governor to see him. He told me that my husband "looked well." This I afterwards found to be false as he had suffered much. Captain Fuller finally obtained a pass for me, and I was allowed to go with him and once more see my husband. I found him a shadow, pale and debilitated. Poor man! here I beheld him in prison, not that he had burned a city, for he had saved Toronto from flames - not that he had taken the lives of his enemies, for he was opposed to the shedding of blood. But he opposed himself to the oppressors of his countrynien - and for this was doomed to suffer death, which sentence was pronounced by Your Honor, and on which occasion, I am informed, you trifled with his feelings and acted the demon.

When I learned the result of the trial I was again permitted to see my husband. Learning that the Governor has been to see him, I was anxious to know the result of the interview. He told me "it would give me no satisfaction to know." I asked him if the Governor spoke kindly? He said "No, he spoke harsh and only added insult to injury. The day before my husband was executed, I, in company with a lady of Toronto, visited the Governor. On entering the room he requested me to sit down - but my errand was of importance. I told him I was the wife of Samuel Lount, and had come before him to plead for mercy. He appeared obstinate, and refused my petition. Thirty-five thousand of his subjects also asked him to interpose his power and save my husband from the sentence of the law. I then kneeled before him in behalf of my husband. With an air of disdain he told me "not to kneel to him, but to kneel to my God!" I replied that I was kneeling in prayer to the Almighty that he would soften his heart. I told him that my husband did not fear to die - that he was prepared for death, but it was his wife and children asking for his life to be spared. To this he sneeringly replied "that if he was prepared for death he might not be so well prepared at another time!" O monster that he was to rule a virtuous people. He said they did not condemn my husband because he was guilty - "I do think," said he, "if Rolph and Mackenzie were here mercy would be shown to them. Two lives were lost at Montgomery's and two must now suffer."

At another time he said "there were others concerned in the rebellion," and intimated that if my husband would expose them he might yet go clear; but my husband always said he would never expose others or bring them into difficulty - the cause they enlisted in was a good one, and before he would expose Mackenzie's Council he would himself be sacrificed.

Thus far neither prayer nor petitions could subdue the hard heart of the Governor, and I gave up my husband as lost to me and Canada. The sad morning came - the victim was led forth - and the endearing husband and father fell a martyr in the cause of Canadian reform. Though thousands had petitioned for his respite that his case might be laid before the Home Government, all was of no avail. Petitions moistened by virtuous tears, nor the humble supplications of an almost heartbroken wife at the feet of the Canadian Governor could touch his heart or move his compassion. Did the law of honor or of justice require this useless flow of blood then I could not censure him. Everything high and honorable, all that was generous and great in Canada, called upon Sir George Arthur to interpose his power and rescue the life of a citizen whom thirty-five thousand Canadians had petitioned to save. Call you this English humanity? Call you him a fit Governor to rule Canada?

Sir, could a tale of human suffering lead you to feel another's woe, I would relate a series of hardships brought upon me and my orphaned children by you, and others of the tory party in Canada, that would call the full grown tears to manly eyes.

Was it for fear of an enraged and insulted people that Governor Arthur refused a defenceless woman the corpse of her murdered husband? No, for that people had no arms to defend themselves with. Why then when upon my bended knee I begged the body of my husband, did he send me from his presence unsatisfied? The wrongs of Canada, and the blood of that innocent man continually preyed upon his mind, and he, like a coward and a tyrant, dared not let my husband's friends behold the iniquitous work he had done. He feared that, when they saw the manly corpses of Lount and Matthews, the generous sympathies of a noble people, who have been too long ruled by threats, might rise, and in retributive justice fall with tenfold force upon himself and those who were his chief advisers.

But, sir, this painful relation is sickening and heart-rending, and I shall close my letter to you that I may draw my mind from the horrible subject. Canada will do justice to his memory. Canadians cannot long remain in bondage. They will be free. The lion will give way, and a bold star will eventually ornament the Canadian standard sheet. Then will the name of Canadian martyrs be sung by poets and extolled by orators, while those who now give law to the bleeding people of Canada will be loathed or forgotten by the civilized world.

And now, by the cruelty of the government, I find myself a widow, driven from home and kindred and a stranger in a strange land. I shall close this letter by saying that my husband, just before his tragic death, said "that he freely forgave them (the tories) for their cruelty, and that he was prepared to meet his God in peace."

Elizabeth Lount

Cite Article : www.canadahistory.com/sections/documents

Source: NAC/ANC, Elgin-Grey Papers